Hi everyone! A little preface: I wrote this piece of research about a year ago. I had for a while wanted to blend my love for historical fashion and my academic background, so I thought it would be fun to do some research. I had an excellent time reading books, articles and researching museum and magazine archives for this. I also created a shorter, more streamlined Youtube video which goes over much of the same facts. I will link that down below. The references and bibliography are at the end.

If you would like to see more videos by all of the wonderful creators participating in CoCoVid, we have a downloadable, printable program just for you, with links directly to each person’s channel! It can be found here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1kqbvE_sdgdZyjHxxwUtC8Pmn_MPAuA7z/view?usp=sharing

If you watch my video on Youtube you’ll also see a link to download a badge and participate in CoCoVid’s online ribbon game!

“My life as a happy one is ended! the world is gone for me! If I must live on (and I will do nothing to make me worse than I am), it is henceforth for our poor fatherless children—for my unhappy country, which has lost all in losing him—and in only doing what I know and feel he would wish, for he is near me—his spirit will guide and inspire me!”[1]

Prince Albert died unexpectedly on the 14th of December in 1861, an event that altered the life of Queen Victoria for the remainder of her years. Her extreme grief was visually apparent by the fact that Queen Victoria remained in mourning dress until she died in 1901. Indeed, the sombre later years of her life are now perceived as her more iconic looks, and the colourful outfits of her youth often forgotten.[2] Mourning dress traditions have existed since ancient times; they have grown and changed throughout the centuries. By the nineteenth century, strict rules were in place. These applied mostly to women’s dress, and depended on the woman’s station and relation to the deceased. Some women never shed mourning dress, like Queen Victoria, once the appropriate mourning period had passed. Mourning dress was an expression of grief, but also a social statement. As Lou Taylor defends, ‘funerals were an ideal stage of a public display of wealth and rank’.[3] The height of mourning dress is often attributed to the decades after Prince Albert’s death, but the tradition seems to almost entirely fade out by the First World War. In this essay, I propose to investigate the social anxieties that the popularisation of these strict rituals instigated, while also keeping in mind the textile and fashion developments of the later Victorian Era and the Early Edwardian Era.

The history of mourning dress is rooted in the human construction of rituals.[4] Due to the public nature of such rituals, mourning dress evolved to display the bearer’s social and economic status.[5] However, mourning dress was also a display of grief, a ritual in itself that helped the mourner cope with loss. A 1900 issue of Vogue subheads ‘Rules for Wearing of Mourning’ with ‘How broken hearts advertise their woe – fashion still makes it obligatory that life’s joylessness shall be made more depressing by exhibition of funereally clad figures in public’.[6] As seen in this description, ‘fashion’ is elevated as its own entity that controls and demands from the mourners. However, there is also an undercurrent tone that suggests this public display is unnecessary. Mourning dress was nearly solely exclusive to women. Men’s mourning dress regulations often only required an arm band.[7] The length and stages of mourning dress were determined by the degree of affiliation of the mourner to the deceased. Widow’s mourning was considered the deepest and longest mourning.[8]

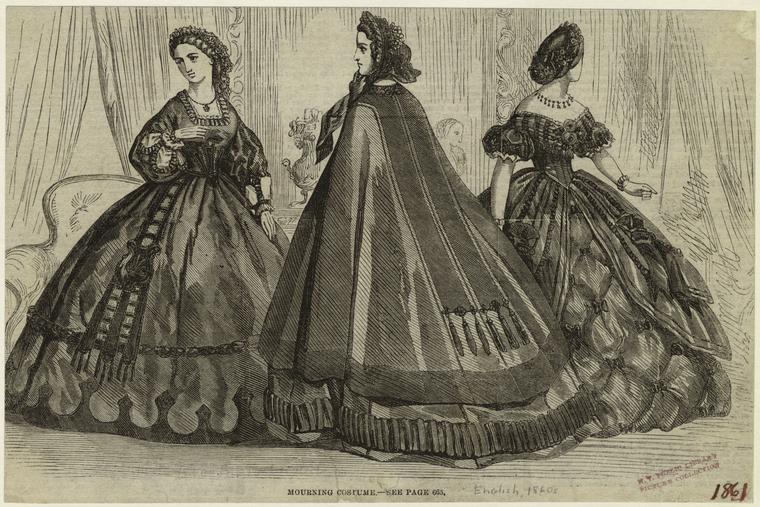

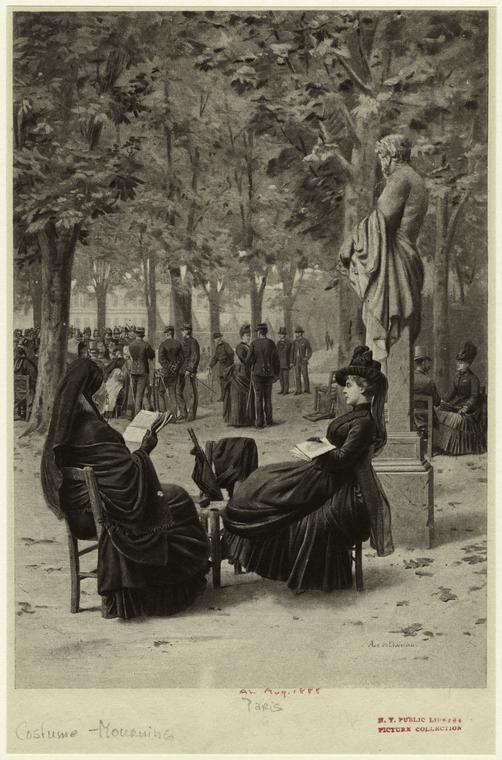

Indeed, the social restrictions of widowhood were also related to the dress itself. Appropriate mourning dress was conventionally simple, though fashionable, and due to the fact that during deepest mourning the mourners were excluded from society, ensured that no dress that challenged these traditions was required. As mourning wear followed fashionable lines, it became more elaborate in the latter half of the nineteenth century. Further along in the mourning period, other colours were introduced. Grey, white, purple and mauve were all very popular for decoration and trims. Dresses entirely of this colour were permissible for half-mourning as well.[9] Therefore, mourning dress was not only regulated by the fashionable style of the time and the social situation, but also the mourning period.

Dressing in mourning was also seen as a matter of propriety for the social lady. As the rules had evolved to be so complex, they were both severe and hard to pinpoint. The rules of mourning seem to have been assumed to be common knowledge, just like knowing the fashionable thing to wear to an important dinner party. Due to the importance of appearances for one’s social status, the rules’ complexity arouse a panoply of anxieties in the fashionable lady. Ladies’ magazines, popularised in the nineteenth century, were flooded with enquiries from concerned readers regarding the appropriate periods of mourning and the appropriate colours, trims and textiles. Vogue, for example, often had enquiries in the ‘Answers to Correspondence’ section, in addition to fashion plates and sections fully dedicated to mourning, which reiterated the rules as these changed. One correspondent writes to Vogue, ‘Am in deep mourning for my sister and have not the least idea what to wear, riding and golfing […] Is it permissible to wear jewelry.’[10] Despite being in mourning, the correspondent is clearly anxious about what is appropriate to wear while in mourning for social but everyday situations, such as golfing and riding. Mourning wear was applicable even to what can be considered the early days of ‘sportswear.’ Often, fashion plates were also included, which showed fashionable silhouettes adapted to mourning wear.

Although mourning wear was an expression of grief, the regulations on women’s clothing during times of grief grew so restricting that often they had to don mourning dress for the faintest of relatives, including ‘the Wives mourned relatives of their husbands as their own and this spread to further complimentary mourning, by a second wife for the first wife’s near relations, and by mothers-in-law for the mothers of their sons and daughters-in-law.’[15] As mourning dress was required for such a wide spread of relations, it is easy to assume that it became fairly common in women’s wardrobes. Not to mention that ‘average life expectancy was less than fifty and death in childbirth or as a child was common.’[16] It was also a sign of respect for the deceased and their grieving family, so it was important to be prepared for these circumstances.

Balancing mourning dress with social pressures was delicate. In particular, the widow was in a difficult position. She was expected to display her grief for at least two years, yet ‘Remarriage would secure their financial protection, a vital necessity for survival in the Victorian/Edwardian eras.’[17] The fact that mourning dress followed current fashionable trends helped keep elegance, femininity and sexual appeal in play. Further, the display of devotion to a departed husband could be seen as desirable, as the widow performed the prescribed societal designs. Here, the rules between the sexes once again stand far apart. Men could remarry as soon as they pleased, even if still in mourning for their first wife. Not only that, but it was tasteful that ‘his new wife should equally associate herself with his mourning’, either in full black or half-mourning dress.[18]

The growing fashionability of mourning dress was remarked in magazines, ‘Have you noticed how very smart mourning dress is nowadays?’.[19] This evolution, from dull plain dresses, was seen as a comfort for some women, who were often unhappy with having to wear dull clothes for so long. However, it was not just a comfort but also a fresh source of anxiety. As clothes started to follow fashion trends more closely after the 1880s, it meant that mourning dresses would have to be changed every few years, as they would be hopelessly out of fashion. Only the highest class and wealthiest ladies could afford to commission new dresses for mourning. Previously, one would have a small selection of mourning wear that would be put away and brought out when required. However, since fashion changed every few years and mourning dress copied it, it was now required to have a new dress for mourning. The regulations on mourning dress made it very expensive to maintain. It became common to sell on mourning dress once the mourning period was over, in an effort to staunch the cost.[20] Some women resisted this. For example, there is a portrait of Mrs. Turner of Ilminster and Taunton in Somerset. The portrait depicts a mourning dress that can be dated 1890-1900, however the portrait was taken in 1909.[21] Some women that could not afford to have new dresses made for mourning often altered existing dresses or dyed already owned dresses black.[22] This was not, however, very incongruous, as the popular cloth for deep mourning was crape, which was solely used for mourning wear. After crape, which was preferred particularly for first mourning, ‘almost any material in black or white or a combination of the two may be worn. Satin is an exception.’[23]Some of the more decadent fabrics, such as velvet, had to be adapted by being expertely combined with white lace or a particular cut to be acceptable.[24]

The reliance on crape, a crinkled lightweight crepe, was the wealth of some, such as the firm of Courtauld, ‘the demand for it in this country by the first mourning establishments is so great that the supply does not always equal the requirement’.[25] A cheaper variety of crape, called the ‘Albert,’ was developed, catering to the lower classes. Yet again the popularisation of mourning dress by Victoria is referenced in the naming of the new cloth. The ‘Albert’ not only boosted existing firms but also specific warehouses and department stores emerged to supply the mourning trade. For example, Nicholsons had a branch called Argyll General Mourning and Mantle Warehouse, in Regent Street.[26] Since mourning dress was now fashionable, could change quickly and the need for it was often unexpected, department stores offered a particular mourning dressmaker service, so that dresses were produced quickly. Prior to this, there was often a period of at least eight days after the bereavement where mourning was not worn, as clothes could not be made up in time.[27] Anne Buck interestingly found that conditions for dressmakers working in the mourning trade were often better than those of general dressmakers.[28] According to Eleri Lynn, a cheap black dye was introduced to the commercial market in the late 1860s. Previously, it had been expensive and unstable to use black dye, as it was made with an iron compound that made fabric disintegrate.[29] This development in the use of dyes may have played a part in propelling the mourning industry, as it was aptly timed with Queen Victoria’s own mourning and the subsequent popularization of the practice. The decline of crape accompanied the decline of mourning dress. Opposition and resistance had been growing since the 1870s, mostly on economic grounds. As seen, funerals and mourning dress came at great expense. The use of crape started to decline in the 1890s, particularly after the Princess of Wales did not wear crape in her mourning for the Duke of Clarence.[30]

Mourning also permeated into other aspects of fashion and everyday life. According to the advice to remain in simple dress, jewellery and accessories were limited. They should follow the directions used for clothing. Jet jewellery became very popular. In the exhibition ‘Victoria: Woman and Crown’ held at Kensington Palace in 2019, Victoria’s mourning is mentioned throughout. One of the extant garments in the exhibition is a bodice from her later years, seen in the bustle fashion. The bodice is decorated with trim made of jet, which adds a fashionable detail while still keeping in line with the regulations for mourning dress. Indeed, the use of jet in mourning dress may be directly connected to the peak in men employed in the sector in 1871, proving how the increase in demand had to be met in production.[31] Featured in the exhibition are different manifestations of mourning, other than dress. One of them can be seen in the painting Queen Victoria at Osborne by Sir Edwin Landseer, dated 1865-67, where not only is Victoria dressed in mourning, but her letters are trimmed with black ribbon as well.[32]

These details were further permeations of mourning into everyday life. For example, while undergarments were not replaced, it was common for decorative aspects, such as ribbons, to be exchanged for black trimmings.[33] These moments of mourning may be seen to relate more closely to mourning traditions as expressions of grief, as with the undergarments, these are excused from public scrutiny.

The last blow to mourning wear was the First World War. The number of casualties was so high that it became impractical, nearly impossible, to enact the previous rules of mourning wear for every known deceased.[34] The wide spread of public mourning also seemed to diminish the effect of it. In conjunction with the financial stress enacted by the war, the added expense of converting or procuring one’s mourning wardrobe was seen as folly. Other parts of mourning etiquette, such as periods of seclusion, were made impossible by women’s participation in the war effort.[35] Taylor also suggests that another reason for the detriment of the traditional mourning rituals during the First World War period and immediately, after may have been due to a distinct patriotic feeling, that rendered the previous mourning rituals unfit to express war-related mourning. For example, Parkes Weber describes ‘some English ladies who had lost sons, husbands or brothers in battle objected to the wearing of ordinary mourning but suggested the use of a purple band on the left arm as a token of the patriotic death of their relatives.’[36] The extraordinary casualties of the First World War left behind what was often described as ‘an army of widows.’[37] Bedikian also expertly connects the advancement of women’s rights and the change of women’s lifestyles after the war with the decline of mourning dress. As I have highlighted above, there was a massive discrepancy between the mourning rituals for men and women. Men were required to wear mourning for three weeks after the death of a spouse, while women had a minimum of two and a half years. It is also seen as a practical decision. As remarriage was often delayed by mourning, widows were often put into precarious situations where they had no financial support.

As I have shown, mourning dress was more than just ‘wearing black’. It became a social symbol of wealth, a source of anxiety and also a way to express grief. It was a socio-cultural minefield, where the dress should be simple to show respect for the deceased – however it was also crucial that it was still fashionable, but subdued enough to be considered ‘in good taste’. Not only in the design itself, but the textile crape evolved to be the marking of mourning dress and bolstered a whole retail industry. The propriety of the length of the mourning period was also highly debated, with women turning to the popular magazines to soothe their anxieties. Mourning became a highly structured ritual, where following the rules was intrinsic to one’s social standing.

Although most of these rules are now obsolete, a legacy of Victorian mourning dress is still visible in the custom of wearing black to publicly signify bereavement. Therefore further investigation into these material cultures can continue to reveal not only insight into the intricate mechanisms of Victorian lives, but will also illuminate how anthropological anxieties are codified and embodied throughout dress history more broadly.

.jpg)

[1] Queen of Great Britain Victoria. The Letters of Queen Victoria, Volume III (of 3), 1854-1861 (Gutenberg, 2009) in Project Gutenberg <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28649/28649-h/28649-h.htm> [accessed 31st of January, 2020], p.473-4.

[2] Taylor, Lou, Mourning Dress (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1983), p. 122.

[3] Taylor, p. 20.

[4] Buck, Anne, ‘The Trap Re-baited: Mourning Dress 1860-1890’ Costume 2 suppl. 1 (1968) p. 32.

[5] Taylor, p. 20.

[6] Anon, ‘Fashion: Rules for Wearing of Mourning’ Vogue Vol. 15, Iss. 6, (Feb 8, 1900), p. vi.

[7] Taylor, p. 134

[8] Buck, p.32

[9] Taylor, p.147

[10] Anon, ‘Answers to Correspondents’ Vogue Vol. 18, Iss. 3, (Jul 18, 1901), p. 47.

[11] Taylor, p. 136.

[12] Taylor, p. 141.

[13] Anon, ‘Features: Answers to Correspondents’ Vogue Vol. 13, Iss. 25, (Dec 29, 1898), p. 424.

[14] Taylor, p. 134.

[15] Buck, p. 33.

[16] Benesh, Carolyn L. E. ‘Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire’, Ornament, vol. 38. No. 1 (2015), p. 21.

[17] Benesh, p. 22.

[18] Abijes, Mme de. Deuil, Ceremonial, Usages, Toilettes (Paris: Grand Maison de Noir, 1885), pp. 27-29.

[19] Taylor, p. 131.

[20] Taylor, p. 132.

[21] Taylor. p. 150.

[22] Taylor, p. 126.

[23] Anon, ‘Answers to Correspondents’, Vogue, Vol. 22, Iss. 4, (Jan 28, 1904), p. 131.

[24] Taylor, p. 157.

[25] Buck. p. 35.

[26] Adburgham, Alison. Shops and Shopping, 1800-1914 (London: Harper Collins, 1981) p. 67.

[27] Taylor, p. 192.

[28] Buck, p. 35.

[29] Lynn, Eleri. Underwear: fashion in detail (London: V&A, 2014), p. 44.

[30] Buck, p. 37.

[31] Hansen, Viveka, ‘Jet and Dressed in Black — The Victorian Period’, 25 September 2017, The Victorian Web <http://www.victorianweb.org/art/costume/mourning/8.html> [accessed 31st of January 2020].

[32] Royal Collection Trust, Queen Victoria at Osborne 1865-67 <https://www.rct.uk/collection/403580/queen-victoria-at-osborne> [accessed 31st of January 2020].

[33]Taylor, p. 252.

[34] Bedikian, Sonia. ‘The Death of Mourning: from Victorian crepe to the Little Black Dress’, Omega , Vol. 57. No. 1 (2008), p. 43.

[35] Taylor, p. 267.

[36] Weber, Parkes. Aspects of Death and Correlated Aspects of Life in Art (Fisher Unwin: London, 1918), p. 427.

[37] Bedikian, p. 47.

Bibliography

Anon, ‘Fashion: Rules for Wearing of Mourning’, Vogue, Vol. 15, Iss. 6, (Feb 8, 1900), p. vi.

Anon, ‘Answers to Correspondents’, Vogue, Vol. 18, Iss. 3, (Jul 18, 1901), p. 47.

Anon, ‘Answers to Correspondents’, Vogue, Vol. 22, Iss. 4, (Jan 28, 1904), p. 131.

Anon, ‘Features: Answers to Correspondents’, Vogue, Vol. 13, Iss. 25, (Dec 29, 1898), p. 424.

Abijes, Mme de. Deuil, Ceremonial, Usages, Toilettes (Paris: Grand Maison de Noir, 1885).

Adburgham, Alison, Shops and Shopping, 1800-1914 (London: Harper Collins, 1981).

Bedikian, Sonia. ‘The Death of Mourning: from Victorian crepe to the Little Black Dress’, Omega , Vol. 57. No. 1 (2008), pp. 35-52.

Benesh, Carolyn L. E. ‘Death Becomes Her: A Century of Mourning Attire’, Ornament, vol. 38. No. 1 (2015) pp. 20-26.

Buck, Anne, ‘The Trap Re-baited: Mourning Dress 1860-1890’, Costume, 2. Suppl. 1 (1968), pp. 32-37.

Hansen, Viveka, ‘Jet and Dressed in Black — The Victorian Period’, 25 September 2017, The Victorian Web <http://www.victorianweb.org/art/costume/mourning/8.html> [accessed 31st of January 2020].

Lynn, Eleri, Underwear: fashion in detail (London: V&A, 2014).

Queen of Great Britain Victoria. The Letters of Queen Victoria, Volume III (of 3), 1854-1861 (Guttenberg, 2009) in Project Guttenberg <http://www.gutenberg.org/files/28649/28649-h/28649-h.htm> [accessed 31st of January, 2020].

Royal Collection Trust, Queen Victoria at Osborne 1865-67 <https://www.rct.uk/collection/403580/queen-victoria-at-osborne> [accessed 31st of January 2020].

Taylor, Lou, Mourning Dress (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1983).

Weber, Parkes. Aspects of Death and Correlated Aspects of Life in Art (Fisher Unwin: London, 1918).